Cybersecurity Lessons for Protecting Critical Infrastructure

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

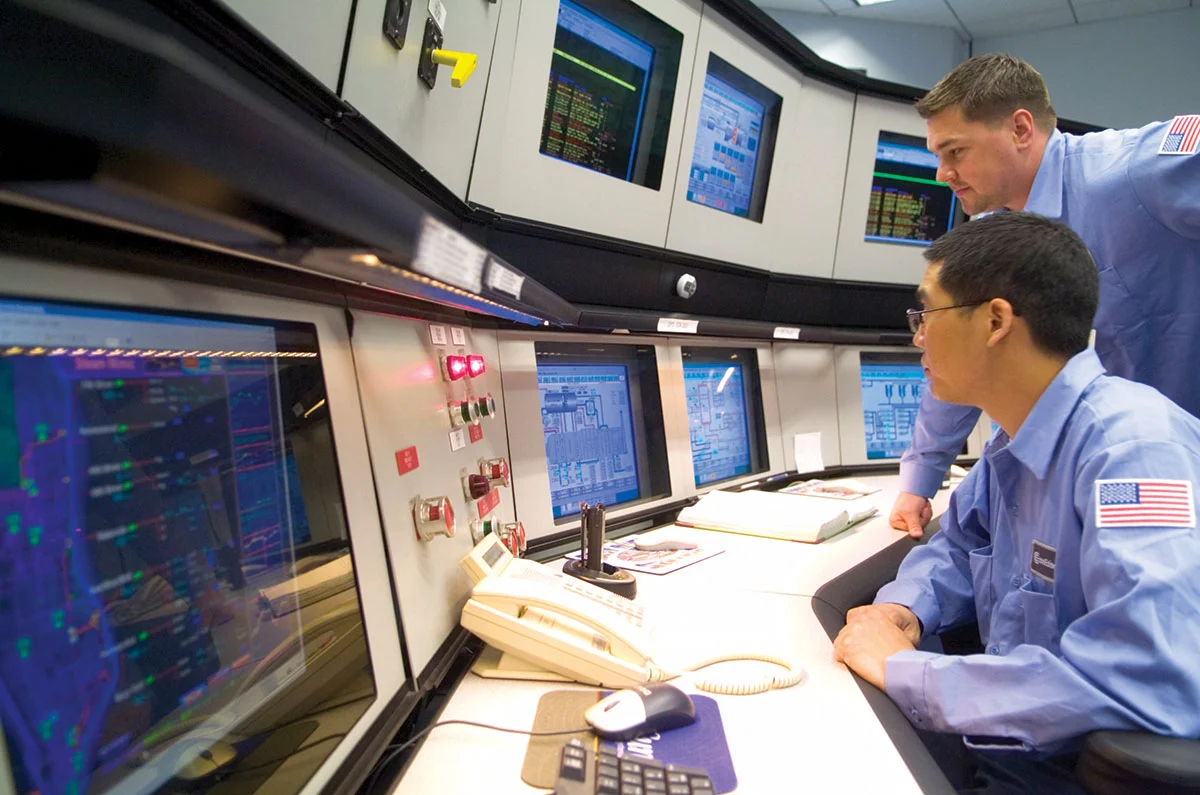

Though it’s been almost two years, the cyber attack on the Ukrainian power grid in December 2015 still reverberates through the power plant community. The attackers took out a quarter of a million homes in the dead of winter, rendering them dark and cold just two days before Christmas. Operators were locked out of their own control systems, helpless to react as they watched the attack unfold on their screens, one system after another coming down. Attackers struck again using different methods a year later.

In response, operators and their vendors here in the U.S. and around the world wasted no time trying to secure their own plants. These actions and the best practices they are employing can also help manufactures in non-critical industries meet the growing threat from cyber attacks against increasingly connected systems.

Siemens, for example, has built a portfolio of operational technology (OT) network infrastructure for its own use, and is now rolling it out to its customers. “We call it First Line of Defense,” says Leo Simonovich, director of global cyber strategy at Siemens. These systems have OT security built in that follows the best practices outlined by others in the industry, including the North American Electric Reliability Corp. (NERC).

Attacks on the rise

The Ukrainian power grid is just one example of the rising number of critical facilities and industrial networks coming under attack across a wide range of industries. Many of these attacks are not specifically targeted at industrial networks, explains Galina Antova, CEO of OT security supplier Claroty. “The industrial networks have been affected by some of the ransomware attacks out there. They were not necessarily targeting the industrial networks, but ended up impacting the industrial networks nonetheless.”

WannaCry, a particularly virulent strain of ransomware—software that encrypts victims’ networks and holds them for ransom—caused widespread harm when it struck in May. Older networks—many of which are industrial networks—are particularly vulnerable to attack. Chocolate maker Mondelez International was one of several manufacturers reporting revenue lost to ransomware in 2017.

Part of what has made these attacks so effective is that cyber criminals now have access to more sophisticated tools than ever before, Antova says. “It’s the first time in history that non-nation-state actors have access to nation-state capabilities,” she says. Following an August 2016 attack on the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA), hackers have distributed tools developed by the spy agency through the digital underground. “Now you’ve got the ultimate weapon; you’ve got a nation-state weapon.”

OT, controlling the machines running manufacturing processes, could be particularly vulnerable to cyber attacks. It is the new risk frontier, Simonovich says. “We’ve seen that those attacks are having big impacts on performance of plants with some pretty scary outcomes.”

Two factors combine to increase risk to OT, Simonovich says. To begin with, many industrial processes lack the readiness that is often more common in the business IT world. “Things like patching, configuration management—the basics, the hygiene,” he says. “The speed and the sophistication of the attacker has also increased.”

It’s no wonder, then, that a recent survey about cybersecurity in the oil and gas industry conducted by the Ponemon Institute and funded by Siemens found that 68 percent of respondents believe their organizations have been compromised by at least one cyber attack.

Fortunately, best practices can go a long way toward mitigating the risk.

Cybersecurity best practices

Cybersecurity for OT has to start at the top—someone in a senior leadership position has to be responsible for cybersecurity, Antova says. The most logical person for the job, she says, is the chief security officer that many organizations already have in place. Typically, an organization will have such a person dedicated to business IT security. “The most effective way is to expand the accountability and responsibility of that person to now also have oversight of the industrial manufacturing networks as well,” she says. Such expansion of duties is only recently being made, according to Antova, but it’s a necessary step.

As Saadi Kermani, business development manager for Wonderware at Schneider Electric, puts it, “If it’s no one’s job, it’s everyone’s problem.”

That includes the business side of any organization, according to Donovan Tindill, senior security consultant at Honeywell Process Solutions. “Security is synonymous with reliability, and those who prioritize cybersecurity will have a competitive advantage,” he says. In other words, bad security is bad for business.

After making sure that proper responsibility and oversight is assigned for OT security, the next step is to go after what Simonovich calls the low hanging fruit of cybersecurity: making sure that industrial control systems are properly patched with the latest software fixes from their vendors. As he points out, one reason the WannaCry ransomware attack was so devastating was because many of the affected organizations were using old systems without the latest patches. “They were not updating and patching as often as they should,” he says of the victims. “And that vulnerability was left wide open—well documented, well fixed, but ignored.”

As for installing patches, OT systems present special challenges because they cannot be shut down suddenly without negatively impacting the processes they’re running. “There are a handful of critical devices that probably can’t be patched without some downtime,” says Jaime Foose, head of the lifecycle support and security solutions organization for Emerson Automation Solutions’ power and water business.

The solution to patching these critical systems is to plan carefully. “You look to do that in an outage window,” Foose says. “You take a short outage, do it in the middle of the night, or a time where it’s least disruptive to the process.” With proper preparation, she says, systems can be patched and rebooted in a controlled manner that doesn’t interfere unduly with the processes they control.

In addition to patching, basic security steps normally undertaken in the business IT world can also help secure industrial systems. Implementing user account controls, installing malware protection—including antivirus software and whitelisting-approved access points to prevent unauthorized access—are all among the measures Emerson recommends. “Those very basic things that are common on our home computers and on our work computers are things that in an industrial control environment are sometimes not adopted,” Foose explains.

In all, Foose breaks down best practices for OT cybersecurity into four broad categories:

- Analyze your system to map out what is on your networks and where it resides. This will help you plan defenses and plug gaps in security.

- Deploy defenses, including closing open ports and services that aren’t needed, installing patches, installing malware protection and making sure backups are in place and regularly updated in case all else fails.

- Monitor your systems for unusual activity and intrusions. Managing alarms and keeping track of them is vital for this to work.

- Incidence response is the final piece of the puzzle, ensuring that plans are in place for use when something does go wrong—which may include natural disasters and other incidents, not just cyber attacks.

Many of these ideas are relatively easy to follow, Foose says, and they are also codified in cybersecurity standards put out by authoritative sources such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). NIST’s Cybersecurity for Internet of Things (IoT) guidance and its Guide to Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Security point the way to more secure systems, Kermani adds.

Lessons from NERC

Of special interest to critical infrastructure is NERC’s critical infrastructure protection (NERC CIP) standards.

If there’s one organization in North America that is especially well equipped to guard against outages cause by cyber attacks and everything else, it’s NERC, which has 50 years of experience keeping the North American electric grid online. NERC’s chief security officer, Marcus Sachs, is unequivocal in his insistence that critical OT systems should remain isolated. “Our standards make that real clear,” he says. “Automate all that you want, but thou shalt not let thy automation touch the Internet.” Though NERC standards don’t dictate how systems should be built, he says, “We don’t want there to be a connection to the Internet. That’s the standard.”

Sachs isn’t against connectivity within an OT environment, whether it’s at a plant or remotely to engineers monitoring it—just against linking it up willy nilly to the outside world. “If you cross-connect the system with the wide open, public, unregulated, wild, wild West that we call the Internet, you run into problems,” he says.

After securing access to the broader Internet, Sachs says best practices call for doing away with a monoculture of connectivity. In other words, if every plant is engineered too similarly to others, it gives hackers the means to replicate their efforts, allowing them to leverage hacks on one installation to gain access to another. “Get the systems diverse so that if there’s failure, it only fails one, maybe two places, but it can’t cascade,” Sachs advises. “It can’t replicate. It can’t go to other systems because they’re different.” Fortunately, he says, the electric grid here in North America is in good shape in this regard.

Finally, Sachs says, it’s important to recognize that cyber attacks are launched by people—people using cyber tools to do their dirty work, but people nevertheless. At the same time, cybersecurity is also managed by people whose tools are important, but who must remain aware of the dangers and how to counteract them. “It’s not devices fighting devices,” he emphasizes. “It’s people fighting people.”

It was apparently a well-funded, well-trained group of cyber criminals who were likely to have been working for the Russian government who took down large portions of the power grid in the Ukraine in 2015 and again in 2016, according to analysis in Wired magazine. In the first attack, hackers were able to gain access to systems controlling circuit breakers because logging into them did not use two-factor authentication. This provided the security hole for the attackers to log in with hijacked credentials that did not have to be verified by other means.

Though the Ukrainian power plants were back online in a matter of hours after the first attack, and within an hour following the second, a clear shot had been fired across the bow of the world’s industries. The takeaway lesson is that cybersecurity for OT cannot be taken for granted.

Courtesy: Automationworld